The Brain of Morbius

| 084 – The Brain of Morbius | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor Who serial | |||

| Cast | |||

Others

| |||

| Production | |||

| Directed by | Christopher Barry | ||

| Written by | "Robin Bland" (Terrance Dicks rewritten by Robert Holmes) | ||

| Script editor | Robert Holmes | ||

| Produced by | Philip Hinchcliffe | ||

| Executive producer(s) | None | ||

| Music by | Dudley Simpson | ||

| Production code | 4K | ||

| Series | Season 13 | ||

| Running time | 4 episodes, 25 minutes each | ||

| First broadcast | 3 January 1976 | ||

| Last broadcast | 24 January 1976 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| |||

The Brain of Morbius is the fifth serial of the 13th season of the British science fiction television series Doctor Who, which was first broadcast in four weekly parts on BBC1 from 3 to 24 January 1976. The screenwriter credit is given to Robin Bland, a pseudonym for writer and former script editor Terrance Dicks, whose original script had been heavily rewritten by his successor as script editor, Robert Holmes. It is the first serial to feature the Sisterhood of Karn.

The serial is considered to have many thematic links to Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein.[1] It is set on the planet Karn, where the surgeon Mehendri Solon (Philip Madoc) seeks to create a body for the Time Lord war criminal Morbius (Stuart Fell and Michael Spice) from parts of other creatures that have come to the planet.

Plot

[edit]The Time Lords drag the TARDIS to the planet Karn, where the mad scientist Solon has his assistant Condo kill shipwrecked travelers to construct an artificial body for the Time Lord criminal Morbius. The Doctor and Sarah Jane Smith find their way to Solon's castle, where Solon welcomes them as a ruse to steal the Doctor's head. Meanwhile, the Sisterhood of Karn discover and steal the TARDIS; their elderly leader, Maren, recognizes it and believes that the Doctor has come to steal their Elixr of Life.

Solon drugs the Doctor and takes him to his lab, but the Sisterhood intervene and take the Doctor for sacrifice. The Doctor tells the group that he felt Morbius' mind while unconscious, but Maren, who witnessed Morbius' execution, denies this. Solon arrives and tries to bargain for the Doctor's head while Sarah secretly cuts the Doctor loose. The three escape, but Maren blinds Sarah; Solon lies that Sarah can only be healed by the elixr. Sarah stumbles into Solon's lab and is harassed by Morbius' disembodied brain; Solon finds her and drags her out. After overhearing him calling Morbius by his name, she locks Solon in the lab and tries to rescue the Doctor, but is recaptured by Condo.

The Doctor warns the Sisterhood about Morbius' survival. They return him to the castle, where Morbius realizes that the Time Lords tracked him down. He forces Solon to immediately place him in the body using an untested artificial head. Condo recognizes his lost arm on the body and attacks Solon, knocking over Morbius' brain; Solon shoots Condo and forces Sarah to assist in his stead. Sarah regains her sight, but is immediately attacked by a berserk Morbius, who kills Condo and a sister before being tranquilised by Solon.

Maren realizes that Solon revived Morbius, giving the Sisterhood permission to attack. Meanwhile, Solon locks the Doctor and Sarah in the lab and repairs Morbius. The Doctor kills him with homemade cyanogen, but Morbius' lungs filter it out. The Doctor defeats Morbius in a mindbending contest, but is gravely injured; the sisters arrive and chase a dazed Morbius off a cliff. Maren allows the sisters to revive the Doctor with the remaining elixr and sacrifices herself to supply it. The Doctor awakes and part ways with the Sisterhood, giving them a firecracker and matches to maintain their eternal flame.

Production

[edit]The original script was written by Terrance Dicks, using some ideas from his script of the stage play Doctor Who and the Daleks in the Seven Keys to Doomsday to a requirement from Hinchcliffe for a story about a human/robot relationship. However, after delivery Dicks was out of the country when it was decided that the robot, core to the story, could not be realised under the budget constraints. In excising the character, script editor Robert Holmes had to undertake the substantial rewrites without informing Dicks, who could not be contacted. The robot character was replaced with Solon who required a different motivation—that of a mad scientist. Dicks later said of the decision that it was not original but it was the "only one available". Upon his return to the United Kingdom, Dicks learnt of the changes and angrily phoned Holmes. Since the work was more Holmes than his own, Dicks demanded the removal of his name from the credits saying it could go out under a "bland pseudonym".[2] This ended up being the name Robin Bland.[2][3] The episodes were recorded entirely in studios during October 1975.

Cast notes

[edit]Philip Madoc had already appeared in The Krotons (1968–69) and The War Games (1969) and would appear afterwards in The Power of Kroll (1978–79). He also had a role in the film Daleks' Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. (1966) and appeared in the audio plays Master and Return of the Krotons. Colin Fay was a fortunate find for the production team: an opera singer by trade, he was a large man and, as a newcomer to television, cheap to hire.[4] Other cost cutting included hiring only a single professional dancer who was copied in the scenes by actresses who had been chosen because of previous dancing experience.

Faces in the mind-bending sequence

[edit]During the Doctor's mental battle with Morbius, the mind-bending machine displays two images of Morbius, then images of the Doctor's four incarnations as of the serial's production. These are followed by images of eight previously unseen faces, intended to represent incarnations preceding the First Doctor. The Doctor's previous faces are almost all portrayed by members of the Doctor Who crew who worked on this serial or the following serial, The Seeds of Doom: production unit manager George Gallaccio, script editor Robert Holmes, production assistant Graeme Harper, director Douglas Camfield, producer Philip Hinchcliffe, production assistant Christopher Baker (who is the exception as he has no credits on Doctor Who), writer Robert Banks Stewart, and director Christopher Barry.[5][6] Hinchcliffe stated, "We tried to get famous actors for the faces of the Doctor. But because no one would volunteer, we had to use backroom boys. And it is true to say that I attempted to imply that William Hartnell was not the first Doctor".[7] After a complaint that actors were not used, the BBC paid a sum of money to the acting union Equity's benevolent fund.[8] In 2020 it was announced that Hinchcliffe, Gallaccio and Harper had returned to reprise theirs roles as the Doctor for a three part unofficial fan video entitled The Timeless Doctors produced by multimedia artist Stuart Humphryes.[9]

The season 14 story The Deadly Assassin introduced the idea that Time Lords are limited to 12 regenerations. The season 10 story The Three Doctors, produced and aired before both The Brain of Morbius and The Deadly Assassin, calls the William Hartnell Doctor the "earliest Doctor". Attempts to retrofit this with the number of faces seen in the mind test machine have brought about explanations including the possibility that the faces were Morbius' previous incarnations, younger versions of the First Doctor, or the Doctor's potential future incarnations.[1][10] The Virgin Missing Adventure Cold Fusion by Lance Parkin implies that one of these prior Doctors was the incarnation of the Doctor active at the time of the birth of Susan Foreman. However, the subsequent Virgin New Adventures novel Lungbarrow states that Hartnell's Doctor was the first, implying instead that the faces represent incarnations of the Other, one of the founders of Time Lord civilisation, of whom the Doctor is the reincarnation.[11]

The series 12 episode "The Timeless Children" (2020) confirmed that the faces were indeed incarnations pre-dating the First Doctor; the same story also confirmed that the Doctor is not subject to the same regeneration limit as the rest of the Time Lords.

Broadcast and reception

[edit]| Episode | Title | Run time | Original air date | UK viewers (millions) [12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Part One" | 25:25 | 3 January 1976 | 9.5 |

| 2 | "Part Two" | 24:46 | 10 January 1976 | 9.3 |

| 3 | "Part Three" | 25:07 | 17 January 1976 | 10.1 |

| 4 | "Part Four" | 24:18 | 24 January 1976 | 10.2 |

Upon the story's original broadcast, Mary Whitehouse (of the National Viewers' and Listeners' Association) complained of the violence displayed; she was quoted saying that The Brain of Morbius "contained some of the sickest and most horrific material seen on children's television".[13] At the time the programme was under close scrutiny by the NVALA; complaints centred on the shooting of Condo by Solon with a resulting spurt of blood.[14]

The story was repeated on BBC1 at 5:50 pm on 4 December 1976, edited and condensed into a one-hour-long omnibus episode.[15] This edit—done without the director's participation—was similar (but not exactly the same) to the one used for the 1984 video release.[14] The omnibus repeat was seen by 10.9 million viewers, a higher audience than the original episodic broadcast.[16]

In 1984, Colin Greenland reviewed The Brain of Morbius for Imagine magazine, and stated that it was "lovely Gothic nonsense, enlivened by spirited characterisation."[17] Paul Cornell, Martin Day, and Keith Topping wrote of the serial in The Discontinuity Guide (1995), "A superb exploration of gothic themes. Philip Madoc's portrayal of Solon is crucial to the story's success, and the pseudonymous epithet 'bland' is not at all deserved."[18] In The Television Companion (1998), David J Howe and Stephen James Walker praised Madoc as Solon and the sets, and noted that the violence was realistic but adult.[13] Together with Mark Stammers in the Fourth Doctor Handbook they described it as "everything a good piece of drama should be: entertaining, enjoyable, effective and emotional".[14] In 2010, Patrick Mulkern of Radio Times awarded it five stars out of five. He noted that Solon's insistence that he only use the Doctor's head was "a fundamental lapse in logic", but otherwise said that the serial was "a salivating treat".[19] The A.V. Club reviewer Christopher Bahn found some minor problems in the script, but gave a positive review of the story, pointing out how it did not rip off classic stories but repurposed them.[20] DVD Talk's David Cornelius gave the serial four out of five stars, saying that it "allows for a wide range of storytelling tones without feeling cluttered or uneven", though at points the "silliness" of the Morbius costume threatened to "overtake" the story.[21]

Commercial releases

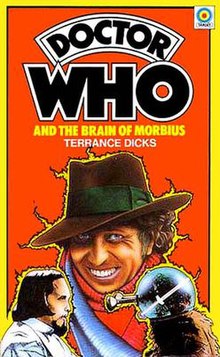

[edit]In print

[edit] | |

| Author | Terrance Dicks |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Mike Little |

| Series | Doctor Who book: Target novelisations |

Release number | 7 |

| Publisher | Target Books |

Publication date | 23 June 1977 |

| ISBN | 0-426-11674-7 |

A novelisation of this serial, written by Terrance Dicks, was published by Target Books in June 1977. An unabridged reading of the novelisation by actor Tom Baker was released on CD in February 2008 by BBC Audiobooks.

Dicks also wrote a second adaptation for younger readers that was published in 1980 as Junior Doctor Who and the Brain of Morbius. A French translation of the full novelisation was published in 1987.

Home media

[edit]The serial was released on VHS in a 59-minute heavily edited omnibus format in July 1984 and complete in episodic form in July 1990.[14] The edited version was also released on Betamax, Video 2000, and Laserdisc. The story was released in complete form on DVD on 21 July 2008.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Howe, David J. & Walker, Steven James (2004). The Television Companion: The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Doctor Who. Springer. ISBN 1-903889-52-9. Archived from the original on 16 February 2006.

- ^ a b Gallagher, William (27 March 2012). "Doctor Who's secret history of codenames revealed". Radio Times. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Howe, Walker and Stammers Doctor Who the Handbook: The Fourth Doctor pp 175-176

- ^ Howe Stammers Walker p182

- ^ How Stammers Walker (1992) p198

- ^ "The Brain of Morbius". BBC. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Lance Parkin, A History of the Universe pg. 255

- ^ Howe, David J., Mark Stammers and Steven James Walker (1992). Doctor Who, The Handbook: The Fourth Doctor. Doctor Who books. ISBN 0-426-20369-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) p198 - ^ "The Timeless Doctors". BabelColour. Stuart Humphryes. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Paul Cornell, Martin Day and Keith Topping's "Doctor Who: The Discontinuity Guide", (Virgin Books, 1995)

- ^ Parkin, Lance; Pearson, Lars (12 November 2012). AHistory: an Unauthorised History of the Doctor Who Universe (3rd Edition). Des Moines: Mad Norwegian Press. p. 715. ISBN 978-193523411-1.

- ^ "Ratings Guide". Doctor Who News. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ a b Howe, David J & Walker, Stephen James (1998). Doctor Who: The Television Companion (1st ed.). London: BBC Books. ISBN 978-0-563-40588-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Howe, Stammers, Walker (1992) p201

- ^ "Dr Who: The Brain of Morbius". The Radio Times (2769): 21. 2 December 1976 – via BBC Genome.

- ^ doctorwhonews.net. "Doctor Who Guide: broadcasting for The Brain of Morbius".

- ^ Greenland, Colin (September 1984). "Fantasy Media". Imagine (review) (18). TSR Hobbies (UK), Ltd.: 47.

- ^ Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1995). "The Brain of Morbius". The Discontinuity Guide. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-426-20442-5.

- ^ Mulkern, Patrick (28 July 2010). "Doctor Who: The Brain of Morbius". Radio Times. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Bahn, Christopher (21 August 2011). "The Brain of Morbius". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Cornelius, David (15 October 2008). "Doctor Who: The Brain of Morbius". DVD Talk. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

External links

[edit]Target novelisation

[edit]- Doctor Who and the Brain of Morbius title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database