Balochi language

| Balochi | |

|---|---|

| بلۏچی Balòci | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [bəˈloːt͡ʃiː] |

| Native to | Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan |

| Region | Balochistan |

| Ethnicity | Baloch |

Native speakers | 8.8 million (2017–2020)[2] |

| Balochi Standard Alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Balochi Academy, Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan Balochi Academy Sarbaz, Sarbaz, Iran |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | bal |

| ISO 639-3 | bal – inclusive codeIndividual codes: bgp – Eastern Balochibgn – Western Balochibcc – Southern Balochi |

| Glottolog | balo1260 |

| Linguasphere | > 58-AAB-aa (East Balochi) + 58-AAB-ab (West Balochi) + 58-AAB-ac (South Balochi) + 58-AAB-ad (Bashkardi) 58-AAB-a > 58-AAB-aa (East Balochi) + 58-AAB-ab (West Balochi) + 58-AAB-ac (South Balochi) + 58-AAB-ad (Bashkardi) |

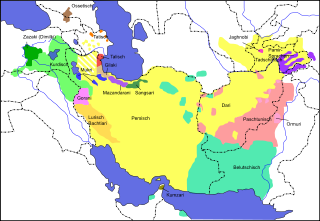

The position of Balochi language among Iranian languages.[1] | |

Balochi (بلۏچی, romanized: Balòci) is a Northwestern Iranian language, spoken primarily in the Balochistan region of Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan. In addition, there are speakers in Oman, the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, Turkmenistan, East Africa and in diaspora communities in other parts of the world.[3] The total number of speakers, according to Ethnologue, is 8.8 million.[2] Of these, 6.28 million are in Pakistan.[4]

According to Brian Spooner,[5]

Literacy for most Baloch-speakers is not in Balochi, but in Urdu in Pakistan and Persian in Afghanistan and Iran. Even now very few Baloch read Balochi, in any of the countries, even though the alphabet in which it is printed is essentially identical to Persian and Urdu.

Balochi belongs to the Western Iranian subgroup, and its original homeland is suggested to be around the central Caspian region.[6]

Classification

[edit]Balochi is an Indo-European language, spoken by the Baloch and belonging to the Indo-Iranian branch of the family. As an Iranian language, it is classified in the Northwestern group.

Glottolog classifies four different varieties, namely Koroshi, Southern Balochi and Western Balochi (grouped under a "Southern-Western Balochi" branch), and Eastern Balochi, all under the "Balochic" group.[7]

ISO 639-3 groups Southern, Eastern, and Western Baloch under the Balochi macrolanguage, keeping Koroshi separate. Balochi, somehow near similarity with the Parthian and on the other hand, it has near kinship to the Avestan.[8][9][10][11][12]

Dialects

[edit]These dialects are broadly categorized into three main groups:[13]

- Eastern group (the Soleimani dialect group): Found mainly in eastern Balochistan, covering parts of Pakistan, particularly in areas like Quetta, Kalat, and Khuzdar.

- Southern group (part of the Makrani dialect group): Spoken in the southern parts of Balochistan, including coastal areas like Gwadar, Chabahar, and southern Pakistan.[13]

- Western group (part of the Rakhshani dialect group) : Predominantly spoken in western Balochistan, including parts of Iran and Afghanistan. Commonly spoken in Sistan and Balochestan province and Khorasan in Iran.[14][13]

Koroshi is also classified as Balochi.[15]

There are two main dialects: the dialect of the Mandwani (northern) tribes and the dialect of the Domki (southern) tribes.[16] The dialectal differences are not very significant.[16] One difference is that grammatical terminations in the northern dialect are less distinct compared with those in the southern tribes.[16] An isolated dialect is Koroshi, which is spoken in the Qashqai tribal confederation in the Fars province. Koroshi distinguishes itself in grammar and lexicon among Balochi varieties.[17]

The Balochi Academy Sarbaz has designed a standard alphabet for Balochi.[18][better source needed]

Phonology

[edit]Vowels

[edit]The Balochi vowel system has at least eight vowels: five long and three short.[19][page needed] These are /aː/, /eː/, /iː/, /oː/, /uː/, /a/, /i/ and /u/. The short vowels have more centralized phonetic quality than the long vowels. The variety spoken in Karachi also has nasalized vowels, most importantly /ẽː/ and /ãː/.[20][page needed] In addition to these eight vowels, Balochi has two vowel glides, that is /aw/ and /ay/.[21]

Consonants

[edit]The following table shows consonants which are common to both Western (Northern) and Southern Balochi.[22][page needed] The consonants /s/, /z/, /n/, /ɾ/ and /l/ are articulated as alveolar in Western Balochi. The plosives /t/ and /d/ are dental in both dialects. The symbol ń is used to denote nasalization of the preceding vowel.[21]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ | t͡ʃ | k | ʔ |

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | d͡ʒ | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | h[b] | ||

| voiced | z | ʒ[c] | |||||

| Rhotic | ɾ | ɽ[d] | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||

In addition, /f/ occurs in a few words in Southern Balochi. /x/ (voiceless velar fricative) in some loanwords in Southern Balochi corresponding to /χ/ (voiceless uvular fricative) in Western Balochi; and /ɣ/ (voiced velar fricative) in some loanwords in Southern Balochi corresponding to /ʁ/ (voiced uvular fricative) in Western Balochi.

In Eastern Balochi, it is noted that the stop and glide consonants may also occur as aspirated allophones in word initial position as [pʰ tʰ ʈʰ t͡ʃʰ kʰ] and [wʱ]. Allophones of stops in postvocalic position include for voiceless stops, [f θ x] and for voiced stops [β ð ɣ]. /n l/ are also dentalized as [n̪ l̪].[23]

Intonation

[edit]Difference between a question and a statement is marked with the tone, when there is no question word. Rising tone marks the question and falling tone the statement.[21] Statements and questions with a question word are characterized by falling intonation at the end of the sentence.[21]

| Language | Example |

|---|---|

| Latin | (Á) wassh ent. |

| Perso-Arabic with Urdu alphabet | .آ) وشّ اِنت) |

| English | He is well. |

| Language | Example |

|---|---|

| Latin | (Taw) kojá raway? |

| Perso-Arabic with Urdu alphabet | تئو) کجا رئوئے؟) |

| English | Where are you going? |

Questions without a question word are characterized by rising intonation at the end of the sentence.[21]

| Language | Example |

|---|---|

| Latin | (Á) wassh ent? |

| Perso-Arabic with Urdu alphabet | آ) وشّ اِنت؟) |

| English | Is he well? |

Both coordinate and subordinate clauses that precede the final clause in the sentence have rising intonation. The final clause in the sentence has falling intonation.[21]

| Language | Example |

|---|---|

| Latin | Shahray kuchah o damkán hechkas gendaga nabut o bázár angat band at. |

| Perso-Arabic with Urdu alphabet | شهرئے کوچه ءُ دمکان هچکَس گندگَ نبوت ءُ بازار انگت بند اَت. |

| English | Nobody was seen in the streets of the town, and the marketplace was still closed. |

Grammar

[edit]The normal word order is subject–object–verb. Like many other Indo-Iranian languages, Balochi also features split ergativity. The subject is marked as nominative except for the past tense constructions where the subject of a transitive verb is marked as oblique and the verb agrees with the object.[24] Balochi, like many Western Iranian languages, has lost the Old Iranian gender distinctions.[6]

Numerals

[edit]Much of the Balochi number system is identical to Persian.[25] According to Mansel Longworth Dames, Balochi writes the first twelve numbers as follows:[26]

| Balochi | Standard Alphabet(Balòrabi) | English |

|---|---|---|

| Yak | یکّ | One[a] |

| Do | دو | Two |

| Sae | سئ | Three |

| Chàr | چار | Four |

| Panch | پنچ | Five |

| Shash | شش | Six |

| Hapt | ھپت | Seven |

| Hasht | ھشت | Eight |

| Noh | نُھ | Nine |

| Dah | دَہ | Ten |

| Yàzhdah | یازدہ | Eleven |

| Dwàzhdah | دوازدھ | Twelve |

| Balochi | Standard Alphabet(Balòrabi) | English |

|---|---|---|

| Awali / Pèsari | اولی / پݔسَری | First |

| Domi | دومی | Second |

| Sayomi | سئیُمی | Third |

| Cháromi | چارمی | Fourth |

| Panchomi | پنچُمی | Fifth |

| Shashomi | شَشُمی | Sixth |

| Haptomi | ھپتُمی | Seventh |

| Hashtomi | ھشتمی | Eighth |

| Nohmi | نُھمی | Ninth |

| Dahomi | دھمی | Tenth |

| Yázdahomi | یازدھمی | Eleventh |

| Dwázdahomi | دوازدھمی | Twelfth |

| Goďďi | گُڈڈی | Last |

- Notes

- ^ The latter ya is with nouns while yak is used by itself.

Writing system

[edit]Balochi was not a written language before the 19th century,[27] and the Persian script was used to write Balochi wherever necessary.[27] However, Balochi was still spoken at the Baloch courts.[citation needed]

British colonial officers first wrote Balochi with the Latin script.[28] Following the creation of Pakistan, Baloch scholars adopted the Persian alphabet. The first collection of poetry in Balochi, Gulbang by Mir Gul Khan Nasir was published in 1951 and incorporated the Arabic Script. It was much later that Sayad Zahoor Shah Hashemi wrote a comprehensive guidance on the usage of Arabic script and standardized it as the Balochi Orthography in Pakistan and Iran. This earned him the title of the 'Father of Balochi'. His guidelines are widely used in Eastern and Western Balochistan. In Afghanistan, Balochi is still written in a modified Arabic script based on Persian.[citation needed]

In 2002, a conference was held to help standardize the script that would be used for Balochi.[29]

Old Balochi Alphabet

[edit]The following alphabet was used by Syed Zahoor Shah Hashmi in his lexicon of Balochi Sayad Ganj (سید گنج) (lit. Sayad's Treasure).[30][31] Until the creation of the Balochi Standard Alphabet, it was by far the most widely used alphabet for writing Balochi, and is still used very frequently.

آ، ا، ب، پ، ت، ٹ، ج، چ، د، ڈ، ر، ز، ژ، س، ش، ک، گ، ل، م، ن، و، ھ ہ، ء، ی ے

Standard Perso-Arabic Alphabet

[edit]| Balochi Standard Alphabet |

|---|

| ا ب پ ت ٹ ج چ د ڈ ر ز ژ س ش ک گ ل م ن و ۏ ہ (ھ) ء ی ے (ݔ) |

|

Extended Perso-Arabic script |

The Balochi Standard Alphabet, standardized by Balochi Academy Sarbaz, consists of 29 letters.[32] It is an extension of the Perso-Arabic script and borrows a few glyphs from Urdu. It is also sometimes referred to as Balo-Rabi or Balòrabi. Today, it is the preferred script to use in a professional setting and by educated folk.

Latin alphabet

[edit]The following Latin-based alphabet was adopted by the International Workshop on "Balochi Roman Orthography" (University of Uppsala, Sweden, 28–30 May 2000).[33]

- Alphabetical order

a á b c d ď e f g ĝ h i í j k l m n o p q r ř s š t ť u ú v w x y z ž ay aw (33 letters and 2 digraphs)

| Letter | IPA | Example words[34] |

|---|---|---|

| A / a | [a] | asp (horse), garm (warm), mard (man) |

| Á / á | [aː] | áp (water), kár (work) |

| B / b (bé) | [b] | barp (snow, ice), bám (dawn), bágpán (gardener), baktáwar (lucky) |

| Ch / ch (ché) | [tʃ] | chamm (eye), bacch (son), kárch (knife) |

| D / d (de) | [d] | dard (pain), drad (rainshower), pád (foot), wád (salt) |

| Dh / dh | [ɖ] | dhawl (shape), gwandh (short), chondh (piece) |

| E / e | [eː] | esh (this), pet (father), bale (but) |

| É / é | éraht (harvest), bér (revenge), shér (tiger) dér (late, delay), dém (face, front), | |

| F / f (fe) | [f] | Only used for loanwords: fármaysí (pharmacy). |

| G / g (ge) | [g] | gapp (talk), ganók (mad), bág (garden), bagg (herd of camels), pádag (foot), Bagdád (Baghdad) |

| Gh / gh | [ɣ] | Like ĝhaen in Perso-Arabic script. Used for loanwords and in eastern dialects: ghair (others), ghali (carpet), ghaza (noise) |

| H / h (he) | [h] | hár (flood), máh (moon), kóh (mountain), mahár (rein), hón (blood) |

| I / i (i) | [iː] | imán (faith), shir (milk), pakir (beggar), samin (breeze), gáli (carpet) |

| J / j (jé) | [dʒ] | jang (war), janag (to beat), jeng (lark), ganj (treasure), sajji (roasted meat) |

| K / k (ké) | [k] | Kermán (Kirman), kárch (knife), nákó (uncle), gwask (calf), kasán (small) |

| L / l (lé) | [l] | láp (stomach), gal (joy), gal (party, organization), goll (cheek), gol (rose) |

| M / m (mé) | [m] | mát (mother), bám (dawn), chamm (eye), master (leader, bigger) |

| N / n (né) | [n] | nagan (bread), nók (new, new moon), dhann (outside), kwahn (old), nákó (uncle) |

| O / o | [u] | oshter (camel), shomá (you), ostád (teacher), gozhn (hunger), boz (goat) |

| Ó / ó (ó) | [oː] | óshtag (to stop), ózhnág (swim), róch (sun), dór (pain), sochag (to burn) |

| P / p (pé) | [p] | Pád (foot), shap (night), shapád (bare-footed), gapp (talk), haptád (70) |

| R / r (ré) | [ɾ] | rék (sand), barag (to take away), sharr (good), sarag (head) |

| Rh / rh (rhé) | [ɽ] | márhi (building), nájórh (sick) |

| S / s (sé) | [s] | sarag (head), kass (someone), kasán (little), bass (enough), ás (fire) |

| Sh / sh (shé) | [ʃ] | shap (night), shád (happy), mésh (sheep), shwánag (shepherd), wašš (happy, tasty) |

| T / t (té) | [t] | tagerd (mat), tahná (alone) tás (bowl), kelitt (key) |

| Th / th (thé) | [ʈ] | thong (hole), thilló (bell), batth (cooked rice), batthág (eggplant) |

| U / u (u) | [uː] | zurag (to take), bezur (take), dur (distant) |

| W / w (wé) | [w] | warag (food, to eat), warden (provision), dawár (abode), wád (salt), kawwás (learned) |

| Y / y (yé) | [j] | yád (remembrance), yár (friend), yázdah (eleven), beryáni (roasted meat), yakk (one) |

| Z / z (zé) | [z] | zarr (monay), zi (yesterday), mozz (wages), móz (banana), nazzíkk (nearby) |

| Zh / zh (zhé) | [ʒ] | zhand (tired), zháng (bells), pazhm (wool), gazzhag (to swell), gozhnag (hungry) |

| Latin digraphs | ||

| Ay / ay | [aj] | ayb (fault), say (three), kay (who) |

| Aw / aw | [aw] | awali (first), hawr (rain), kawl (promise), gawk (neck) |

Soviet alphabet

[edit]In 1933, the Soviet Union adopted a Latin-based alphabet for Balochi as follows:

| a | ə | ʙ | c | ç | d | ᶁ | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | ʟ | |

| m | n | o | p | q | ʼ | r | s | t | ƫ | u | v | w | x | z | ƶ |

The alphabet was used for several texts, including children's books, newspapers, and ideological works. In 1938, however, the official use of Balochi was discontinued.[35]

Cyrillic alphabet

[edit]In 1989, Mammad Sherdil, a teacher from the Turkmen SSR, approached Balochi language researcher Sergei Axenov with the idea of creating a Cyrillic-based alphabet for Balochi. Before this, the Cyrillic script was already used for writing Balochi and was used in several publications but the alphabet was not standardized. In 1990, the alphabet was finished. It included the following letters:

| а | а̄ | б | в | г | ғ | д | д̨ | е | ё | ж | җ | з | и | ӣ | й | к | қ | л | м | н |

| о | п | р | ꝑ | с | т | т̵ | у | ӯ | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

The project was approved with some minor changes (қ, ꝑ, and ы were removed due to the rarity of those sounds in Balochi, and о̄ was added). From 1992 to 1993, several primary school textbooks were printed in this script. In the early 2000s, the script fell out of use.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ "worldhistory". titus.fkidg1.uni-frankfurt.de. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b Balochi at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Eastern Balochi at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Western Balochi at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

Southern Balochi at Ethnologue (26th ed., 2023)

- ^ Spooner, Brian (2011). "10. Balochi: Towards a Biography of the Language". In Schiffman, Harold F. (ed.). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors. Brill. p. 319. ISBN 978-9004201453.

It [Balochi] is spoken by three to five million people in Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan, Oman and the Persian Gulf states, Turkmenistan, East Africa, and diaspora communities in other parts of the world.

- ^ "Table 11 – Population by Mother Tongue, Sex and Rural/Urban" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Spooner, Brian (2011). "10. Balochi: Towards a Biography of the Language". In Schiffman, Harold F. (ed.). Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors. Brill. p. 320. ISBN 978-9004201453.

- ^ a b Elfenbein, J. (1988). "Baluchistan iii. Baluchi Language and Literature". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Glottolog 4.3 – Balochic". glottolog.org. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Towards a Historical Grammar of Balochi : Studies in Balochi Historical Phonology and Vocabulary" (PDF). Open University. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Discourse Features in Balochi of Sistan: (Oral Narratives)". Uppsala University. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "An Old Phonological Study of Balochi and Persian". ResearchGate. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Getting to know the dialects of Sistan and Baluchistan; from north to south". Hamshahri (in Persian). 14 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "A discussion in Iranian linguistics" (in Persian). Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Balochi Language Project". Uppsala University. Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ Sedighi, Anousha (2023). Iranian and Minority Languages at Home and in Diaspora. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110694314.

- ^ Ethnologue report for Southwestern Iranian languages

- ^ a b c Dames 1922, p. 1.

- ^ Borjian, Habib (December 2014). "The Balochi dialect of the Korosh". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 67 (4): 453–465. doi:10.1556/AOrient.67.2014.4.4.

- ^ "Main Balochi Language( Rèdagèn Balòci Zubàn )". Balochi Academy Sarbaz. 16 February 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Farrell 1990. Serge 2006.

- ^ Farrell 1990.

- ^ a b c d e f Jahani, Carina (2019). A Grammar of Modern Standard Balochi. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- ^ Serge 2006. Farrell 1990.

- ^ JahaniKorn 2009, pp. 634–692.

- ^ "Balochi". National Virtual Translation Center. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Korn, Agnes (2006). "Counting Sheep and Camels in Balochi". Indoiranskoe jazykoznanie i tipologija jazykovyx situacij. Sbornik statej k 75-letiju professora A. L. Grjunberga (1930–1995). Nauka. pp. 201–212. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Dames 1922, pp. 13–15.

- ^ a b Dames 1922, p. 3.

- ^ Hussain, Sajid (18 March 2016). "Faith and politics of Balochi script". Balochistan Times. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Script for Balochi language discussed". Dawn. Quetta. 28 October 2002. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Shah Hashemi, Sayad Zahoor. "The First Complete Balochi Dictionary". Sayad Ganj. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Sayad Zahoor Shah Hashmi: A one-man institution". Balochistan Times. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Balochi Standarded Alphabet". BalochiAcademy.ir. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "Baluchi Roman ORTHOGRAPHY". Phrasebase.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- ^ Jahani, Carina (2019). A grammar of modern standard Balochi. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Iranica Upsaliensia. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet. ISBN 978-91-513-0820-3.

- ^ Axenov, Sergei (2000). Language in Society: Eight Sociolinguistic Essays on Balochi. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Iranica Upsaliensia. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet. pp. 71–78. ISBN 91-554-4679-5.

- ^ Kokaislova P., Kokaisl P. (2012). Центральная Азия и Кавказ (in Russian). ISSN 1403-7068.

Bibliography

[edit]- Dames, Mansel Longworth (1922). A Text Book of the Balochi Language: Consisting of Miscellaneous Stories, Legends, Poems, and a Balochi-English Vocabulary. Lahore: Punjab Government Press. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Farrell, Tim (1990). Basic Balochi: an introductory course. Naples: Università degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale". OCLC 40953807.

- Jahani, Carina; Korn, Agnes (2009). "Balochi". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian languages. Routledge Language Family Series (1st ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 634–692. ISBN 978-0-7007-1131-4.

- Serge, Axenov (2006). The Balochi language of Turkmenistan: a corpus based grammatical description. Stockholm: Uppsala Universitet. ISBN 978-91-554-6766-1. OCLC 82163314.

- Jahani, Carina; Korn, Agnes, eds. (2003). The Baloch and Their Neighbours: Ethnic and Linguistic Contact in Balochistan in Historical and Modern Times. In cooperation with Gunilla Gren-Eklund. Wiesbaden: Reichert. ISBN 978-3-89500-366-0. OCLC 55149070.

- Jahani, Carina, ed. (2000). Language in society: eight sociolinguistic essays on Balochi. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-554-4679-6. OCLC 44509598.

Further reading

[edit]- Dictionaries and lexicographical works

- Gilbertson, George W. 1925. English-Balochi colloquial dictionary. Hertford: Stephen Austin & Sons.

- Ahmad, K. 1985. Baluchi Glossary: A Baluchi-English Glossary: Elementary Level. Dunwoody Press.

- Badal Khan, S. 1990. Mán Balócíá Darí Zubánání Judá. Labzánk Vol. 1(3): pp. 11–15.

- Abdulrrahman Pahwal. 2007. Balochi Gálband: Balochi/Pashto/Dari/English Dictionary. Peshawar: Al-Azhar Book Co. p. 374.

- Mír Ahmad Dihání. 2000. Mír Ganj: Balócí/Balócí/Urdú. Karachi: Balóc Ittihád Adabí Akedimí. p. 427.

- Bruce, R. I. 1874. Manual and Vocabulary of the Beluchi Dialect. Lahore: Government Civil Secretariat Press. vi 154 p.

- Ishák Xámúś. 2014. Balochi Dictionary: Balochi/Urdu/English. Karachi: Aataar Publications. p. 444.

- Nágumán. 2011. Balócí Gál: Ambáre Nókáz (Balochi/English/Urdu). Básk. p. 245.

- Nágumán. 2014. Jutgál. Makkurán: Nigwar Labzánkí Majlis. p. 64.

- Ghulám Razá Azarlí. 2016. Farhange Kúcak: Pársí/Balúcí. Pársí Anjuman.

- Hashmi, S. Z. S. 2000. Sayad Ganj: Balochi-Balochi Dictionary. Karachi: Sayad Hashmi Academy. P. 887.

- Ulfat Nasím. 2005. Tibbí Lughat. Balócí Akademí. p. 260.

- Gulzár Xán Marí. 2005. Gwaśtin. Balócí Akedimí. p. 466.

- Raśíd Xán. 2010. Batal, Guśtin, Puźdánk, Ghanŧ. Tump: Wafá Labzání Majlis. p. 400.

- Śe Ragám. 2012. Batal, Gwaśtin u Gálband. Balócí Akademí. p. 268.

- Abdul Azíz Daolatí Baxśán. 1388. Nám u Ném Nám: Farhang Námhá Balúcí. Tihrán: Pázína. p. 180.

- Nazeer Dawood. 2007. Balochi into English Dictionary. Gwádar: Drad Publications. p. 208.

- Abdul Kaiúm Balóc. 2005. Balócí Búmíá. Balócí Akademí. p. 405.

- Ján Mahmad Daśtí. 2015. Balócí Labz Balad [Balochi/Balochi Dictionary]. Balócí Akademí. p. 1255.

- Bogoljubov, Mixail, et al. (eds.). Indoiranskoe jazykoznanie i tipologija jazykovyx situacij. Sbornik statej k 75-letiju professora A. L. Gryunberga. St. Pétersbourg (Nauka). pp. 201–212.

- Marri, M. K. and Marri, S. K. 1970. Balúcí-Urdú Lughat. Quetta: Balochi Academy. 332 p.

- Mayer, T. J. L. 1900. English-Baluchi Dictionary. Lahore: Government Press.

- Orthography

- Jahani, Carina. 1990. Standardization and orthography in the Balochi language. Studia Iranica Upsaliensia. Uppsala, Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksell Internat.

- Sayad Háśumí. 1964. Balócí Syáhag u Rást Nibíssag. Dabai: Sayad Háśumí Balóc. p. 144.

- Ghaos Bahár. 1998. Balócí Lékwaŕ. Balócí Akademí. p. 227.

- Ziá Balóc. 2015. Balócí Rást Nibíssí. Raísí Cáp u Śingjáh. p. 264.

- Axtar Nadím. 1997. Nibiśta Ráhband. Balócí Akedimí. p. 206.

- Táj Balóc. 2015. Sarámad (Roman Orthography). Bahren: Balóc Kalab. p. 110.

- Courses and study guides

- Barker, Muhammad A. and Aaqil Khan Mengal. 1969. A course in Baluchi. Montreal: McGill University.

- Collett, Nigel A. 1986. A Grammar, Phrase-book, and Vocabulary of Baluchi (As Spoken in the Sultanate of Oman). Abingdon: Burgess & Son.

- Natawa, T. 1981. Baluchi (Asian and African Grammatical Manuals 17b). Tokyo. 351 p.

- Munazzih Batúl Baóc. 2008. Ásán Balúcí Bólcál. Balócí Akademí. p. 152.

- Abdul Azíz Jázimí. Balócí Gappe Káidaián. p. 32.

- Muhammad Zarrín Nigár. Dastúr Tatbíkí Zabáne Balúcí bá Fársí. Íránśahr: Bunyáde Naśre Farhange Balóc. p. 136.

- Gilbertson, George W. 1923. The Balochi language. A grammar and manual. Hertford: Stephen Austin & Sons.

- Bugti, A. M. 1978. Balócí-Urdú Bólcál. Quetta: Kalat Publications.

- Ayyúb Ayyúbí. 1381. Dastúr Zabán Fársí bih Balúcí. Íránśahr: Intiśárát Asátír. p. 200.

- Hitturam, R. B. 1881. Biluchi Nameh: A Text-book of the Biluchi Language. Lahore.

- Etymological and historical studies

- Elfenbein, J. 1985. Balochi from Khotan. In: Studia Iranica. Vol. XIV (2): 223–238.

- Gladstone, C. E. 1874. Biluchi Handbook. Lahore.

- Hashmi, S. Z. S. 1986. Balúcí Zabán va Adab kí Táríx [The History of Balochi language and Literature: A Survey]. Karachi: Sayad Hashmi Academy.

- Korn, A. 2005. Towards a Historical Grammar of Balochi. Studies in Balochi Historical Phonology and Vocabulary [Beiträge zur Iranistik 26]. Wiesbaden (Reichert).

- Korn, A. 2009. The Ergative System in Balochi from a Typological Perspective // Iranian Journal for Applied Language Studies I. pp. 43–79.

- Korn, A. 2003. The Outcome of Proto-Iranian *ṛ in Balochi // Iran : Questions et connaissances. Actes du IVe congrès européen des études iraniennes, organisé par la Societas Iranologica Europaea, Paris, 6–10 septembre 1999. III : Cultures et sociétés contemporaines, éd. Bernard HOURCADE [Studia Iranica Cahier 27]. Leuven (Peeters). pp. 65–75.

- Mengal, A. K. 1990. A Persian-Pahlavi-Balochi Vocabulary I (A-C). Quetta: Balochi Academy.

- Morgenstiene, G. 1932. Notes on Balochi Etymology. Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap. p. 37–53.

- Moshkalo, V. V. 1988. Reflections of the Old Iranian Preverbs on the Baluchi Verbs. Naples: Newsletter of Baluchistan Studies. No. 5: pp. 71–74.

- Moshkalo, V. V. 1991. Beludzskij Jazyk. In: Osnovy Iranskogo Jazykozanija. Novoiranskie Jazyki I. Moscow. p. 5–90.

- Dialectology

- Dames, M. L. 1881. A Sketch of the Northern Balochi Language. Calcutta: The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- Elfenbein, J. 1966. The Baluchi Language. A Dialectology with Text. London.

- Filipone, E. 1990. Organization of Space: Cognitive Models and Baluchi Dialectology. Newsletter of Baluchistan Studies. Naples. Vol. 7: pp. 29–39.

- Gafferberg, E. G. 1969. Beludzhi Turkmenskoi. SSR: Ocherki Khoziaistva Material'oni Kultuy I Byta. sn.

- Geiger, W. 1889. Etymologie des Baluci. Abhandlungen der I. Classe der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Vol. XIX(I): pp. 105–53.

- Marston, E. W. 1877. Grammar and Vocabulary of the Mekranee Beloochee Dialect. Bombay.

- Pierce, E. 1874. A Description of the Mekranee-Beloochee Dialect. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. XI: 1–98.

- Pierce, E. 1875. Makrani Balochi. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 11: N. 31.

- Rossi, A. V. 1979. Phonemics in Balochi and Modern Dialectology. Naples: Instituto Universitario Orientale, Dipartimento di Studi Asiatici. Iranica, pp. 161–232.

- Rahman, T. 1996. The Balochi/Brahvi Language Movements in Pakistan. Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. 19(3): 71–88.

- Rahman, T. 2001. The Learning of Balochi and Brahvi in Pakistan. Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. 24(4): 45–59.

- Rahman, T. 2002. Language Teaching and Power in Pakistan. Indian Social Science Review. 5(1): 45–61.

- Language contact

- Elfenbein, J. 1982. Notes on the Balochi-Brahui Linguistic Commensality. In: TPhS, pp. 77–98.

- Foxton, W. 1985. Arabic/Baluchi Bilingualism in Oman. Naples: Newsletter of Baluchistan Studies. N. 2 pp. 31–39.

- Natawa, T. 1970. The Baluchis in Afghanistan and their Language. pp. II:417-18. In: Endo, B. et al. Proceedings, VIIIth International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, 1968, Tokyo and Kyoto. Tokyo: Science Council of Japan.

- Rzehak, L. 1995. Menschen des Rückens – Menschen des Bauches: Sprache und Wirklichkeit im Verwandtschaftssystem der Belutschen. pp. 207–229. In: Reck, C. & Zieme, P. (ed.); Iran und Turfan. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Elfenbein, Josef. 1997. "Balochi Phonology". In Kaye, Alan S. Phonologies of Asia and Africa. 1. pp. 761–776.

- Farideh Okati. 2012. The Vowel Systems of Five Iranian Balochi Dialects. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Studia linguistica Upsaliensia. p. 241.

- Grammar and morphology

- Farrell, Tim. 1989. A study of ergativity in Balochi.' M.A. thesis: School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London.

- Farrell, Tim. 1995. Fading ergativity? A study of ergativity in Balochi. In David C. Bennett, Theodora Bynon & B. George Hewitt (eds.), Subject, voice, and ergativity: Selected essays, 218–243. London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

- Korn, Agnes. 2009. Marking of arguments in Balochi ergative and mixed constructions. In Simin Karimi, VIda Samiian & Donald Stilo (eds.) Aspects of Iranian Linguistics, 249–276. Newcastle upon Tyne (UK): Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Abraham, W. 1996. The Aspect-Case Typology Correlation: Perfectivity Triggering Split Ergativity. Folia Linguistica Vol. 30 (1–2): pp. 5–34.

- Ahmadzai, N. K. B. M. 1984. The Grammar of Balochi Language. Quetta: Balochi Academy, iii, 193 p.

- Andronov, M. S. 2001. A Grammar of the Balochi Language in Comparative Treatment. Munich.

- Bashir, E. L. 1991. A Contrastive Analysis of Balochi and Urdu. Washington, D.C. Academy for Educational Development, xxiii, 333 p.

- Jahani, C. (1994). "Notes on the Use of Genitive Construction Versus Izafa Construction in Iranian Balochi". Studia Iranica. 23 (2): 285–98. doi:10.2143/SI.23.2.2014308.

- Jahani, C. (1999). "Persian Influence on Some Verbal Constructions in Iranian Balochi". Studia Iranica. 28 (1): 123–143. doi:10.2143/SI.28.1.2003920.

- Korn, A. (2008). "A New Locative Case in Turkmenistan Balochi". Iran and the Caucasus. 12: 83–99. doi:10.1163/157338408X326226.

- Jahani, Carina. A Grammar of Modern Standard Balochi. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2019. ISBN 978-91-513-0820-3.

- Leech, R. 1838. Grammar of the Balochky Language. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. VII(2): p. 608.

- Mockler, E. 1877. Introduction to a Grammar of the Balochee Language. London.

- Nasir, K. A. B. M. 1975. Balócí Kárgónag. Quetta.

- Sabir, A. R. 1995. Morphological Similarities in Brahui and Balochi Languages. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. Vol. 24(1): 1–8.

- Semantics

- Elfenbein, J. 1992. Measurement of Time and Space in Balochi. Studia Iranica, Vol. 21(2): pp. 247–254.

- Filipone, E. 1996. Spatial Models and Locative Expressions in Baluchi. Naples: Instituto Universitario Orietale, Dipartimento di Studi Asiatici. 427 p.

- Miscellaneous and surveys

- Baloch, B. A. 1986. Balochi: On the Move. In: Mustada, Zubeida, ed. The South Asian Century: 1900–1999. Karachi: Oxford University Press. pp. 163–167.

- Bausani, A. 1971. Baluchi Language and Literature. Mahfil: A Quarterly of South Asian Literature, Vol. 7 (1–2): pp. 43–54.

- Munazzih Batúl Baóc. 2008. Ásán Balúcí Bólcál. Balócí Akademí. p. 633–644.

- Elfenbein, J. 1989. Balochi. In: SCHMITT, pp. 350–362.

- Geiger, W. 1901. Die Sprache der Balutschen. Geiger/Kuhn II, P. 231–248, Gelb, I. J. 1970. Makkan and Meluḫḫa in Early Mesopotamian Sources. Revue d'Assyriologie. Vol. LXIV: pp. 1–8.

- Gichky, N. 1986. Baluchi Language and its Early Literature. Newsletter of Baluchistan Studies. No. 3, pp. 17–24.

- Grierson, G. A. 1921. Balochi. In: Linguistic Survey of India X: Specimens of Languages of Eranian Family. Calcutta. pp. 327–451.

- Ibragimov, B. 1973. Beludzhi Pakistana. Sots.-ekon. Polozhenie v Pakist. Beludhistane I nats. dvizhnie beludzhei v 1947–1970. Moskva. 143 p.

- Jaffrey, A. A. 1964. New Trends in the Balochi Language. Bulletin of the Ancient Iranian Cultural Society. Vol. 1(3): 14–26.

- Jahani, C. Balochi. In: Garry, J. and Rubino, C. (eds.). Facts About World's Languages. New York: H. W. Wilson Company. pp. 59–64.

- Kamil Al-Qadri, S. M. 1969. Baluchi Language and Literature. Pakistan Quarterly. Vol. 17: pp. 60–65.

- Morgenstiene, G. 1969. The Baluchi Language. Pakistan Quarterly. Vol. 17: 56–59.

- Nasir, G. K. 1946. Riyásat Kalát kí Kaumí Zabán. Bolan.

- Rooman, A. 1967. A Brief Survey of Baluchi Literature and Language. Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. Vol. 15: 253–272.

- Rossi, A. V. 1982–1983. Linguistic Inquiries in Baluchistan Towards Integrated Methodologies. Naples: Newsletter of Baluchistan Studies. N.1: 51–66.

- Zarubin, I. 1930. Beiträge zum Studium von Sprache und Folklore der Belutschen. Zapiski Kollegii Vostokovedov. Vol. 5: 653–679.

External links

[edit] Media related to Balochi language at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Balochi language at Wikimedia Commons- Collett, N. A. A grammar, phrase book and vocabulary of Baluchi: (as spoken in the Sultanate of Oman). 2nd ed. [Camberley]: [N.A. Collett], 1986.

- Dames, Mansel Longworth. A sketch of the northern Balochi language, containing a grammar, vocabulary and specimens of the language. Calcutta: Asiatic Society, 1881.

- Mumtaz Ahmad. Baluchi glossary: a Baluchi-English glossary: elementary level. Kensington, Md.: Dunwoody Press, 1985.

- EuroBalúči online translation tool – translate Balochi words to or from English, Persian, Spanish, Finnish and Swedish

- iJunoon English to Balochi Dictionary

- EuroBalúči – Baluchi alphabet, grammar and music

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Jahani, C. 2019. A Grammar of Modern Standard Balochi