Barium sulfide

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.040.180 |

| EC Number |

|

| 13627 | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| BaS | |

| Molar mass | 169.39 g/mol |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Density | 4.25 g/cm3 [1] |

| Melting point | 2,235[2] °C (4,055 °F; 2,508 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| 2.88 g/100 mL (0 °C) 7.68 g/100 mL (20 °C) 60.3 g/100 mL (100 °C) (reacts) | |

| Solubility | insoluble in alcohol |

Refractive index (nD)

|

2.155 |

| Structure | |

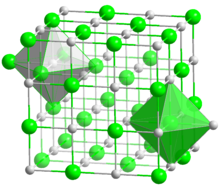

| Halite (cubic), cF8 | |

| Fm3m, No. 225 | |

| Octahedral (Ba2+); octahedral (S2−) | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H315, H319, H335, H400 | |

| P261, P264, P271, P273, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P321, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P391, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

226 mg/kg humans |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Barium oxide Barium selenide Barium telluride Barium polonide |

Other cations

|

Beryllium sulfide Magnesium sulfide Calcium sulfide Strontium sulfide Radium sulfide |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Barium sulfide is the inorganic compound with the formula BaS. BaS is the barium compound produced on the largest scale.[3] It is an important precursor to other barium compounds including BaCO3 and the pigment lithopone, ZnS/BaSO4.[4] Like other chalcogenides of the alkaline earth metals, BaS is a short wavelength emitter for electronic displays.[5] It is colorless, although like many sulfides, it is commonly obtained in impure colored forms.

Discovery

[edit]BaS was prepared by the Italian alchemist Vincenzo Cascariolo (also known as Vincentius or Vincentinus Casciarolus or Casciorolus, 1571–1624) via the thermo-chemical reduction of BaSO4 (available as the mineral barite).[6] It is currently manufactured by an improved version of Cascariolo's process using coke in place of flour and charcoal. This kind of conversion is called a carbothermic reaction:

- BaSO4 + 2C → BaS + 2CO2

and also:

- BaSO4 + 4C → BaS + 4CO

The basic method remains in use today. BaS dissolves in water. These aqueous solutions, when treated with sodium carbonate or carbon dioxide, give a white solid of barium carbonate, a source material for many commercial barium compounds.[7]

According to Harvey (1957),[8] in 1603, Vincenzo Cascariolo used barite, found at the bottom of Mount Paterno near Bologna, in one of his non-fruitful attempts to produce gold. After grinding and heating the mineral with charcoal under reducing conditions, he obtained a persistent luminescent material that soon came to be known as Lapis Boloniensis, or Bolognian stone.[9][10] The phosphorescence of the material obtained by Casciarolo made it a curiosity.[11][12][13]

Preparation

[edit]A modern procedure proceeds from barium carbonate:[14]

- BaCO3 + H2S → BaS + H2O + CO2

BaS crystallizes with the NaCl structure, featuring octahedral Ba2+ and S2− centres.

The observed melting point of barium sulfide is highly sensitive to impurities.[2]

Safety

[edit]BaS is quite poisonous, as are related sulfides, such as CaS, which evolve toxic hydrogen sulfide upon contact with water.

References

[edit]- ^ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ^ a b Stinn, C., Nose, K., Okabe, T. et al. Metall and Materi Trans B (2017) 48: 2922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-017-1107-5 Archived 2024-01-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. "Inorganic Chemistry" Academic Press: San Diego, 2001. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ Vij, D. R.; Singh, N. (1992). Optical and electrical properties of II-VI wide gap semiconducting barium sulfide. Conf. Phys. Technol. Semicond. Devices Integr. Circuits, 1992. Proceedings of SPIE. Vol. 1523. pp. 608–612. Bibcode:1992SPIE.1523..608V. doi:10.1117/12.634082.

- ^ F. Licetus, Litheosphorus, sive de lapide Bononiensi lucem in se conceptam ab ambiente claro mox in tenebris mire conservante, Utini, ex typ. N. Schiratti, 1640. See http://www.chem.leeds.ac.uk/delights/texts/Demonstration_21.htm Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kresse, Robert; Baudis, Ulrich; Jäger, Paul; Riechers, H. Hermann; Wagner, Heinz; Winkler, Jochen; Wolf, Hans Uwe (2007). "Barium and Barium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_325.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Harvey E. Newton (1957). A History of Luminescence: From the Earliest Times until 1900. Memoirs of the American Physical Society, Philadelphia, J. H. FURST Company, Baltimore, Maryland (USA), Vol. 44, Chapter 1, pp. 11-43.

- ^ Smet, Philippe F.; Moreels, Iwan; Hens, Zeger; Poelman, Dirk (2010). "Luminescence in Sulfides: A Rich History and a Bright Future". Materials. 3 (4): 2834–2883. Bibcode:2010Mate....3.2834S. doi:10.3390/ma3042834. hdl:1854/LU-1243707. ISSN 1996-1944.

- ^ Hardev Singh Virk (2014). "History of Luminescence from Ancient to Modern Times". ResearchGate. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Lapis Boloniensis". www.zeno.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Lemery, Nicolas (1714). Trait℗e universel des drogues simples.

- ^ Ozanam, Jacques; Montucla, Jean Etienne; Hutton, Charles (1814). Recreations in mathematics and natural philosophy .

- ^ P. Ehrlich (1963). "Alkaline Earth Metals". In G. Brauer (ed.). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd Ed. Vol. 2pages=937. NY, NY: Academic Press.